I have an issue with the term science which seems increasingly to be used as a synonym for immutable truth:- science tells us…., following the science…., according to science…. etc.

This has been very evident in recent months watching broadcasts where senior Government Ministers update us periodically on the unfolding covid situation in our nation, flanked by senior medics referencing graphs which illustrate the ‘facts’. Some of these professors and public health leaders have become familiar to us over time. We look to them for reassurance and credibility when our Prime Minister or members of his Cabinet are challenged on policy by sceptical journalists and naïve members of the public, live on air. Their numbers do not lie. If we don’t trust the PM, we must at least have confidence in the scientists? But there is a problem, it appears that scientists sometimes disagree. Seemingly, one scientist’s truth may not always match that of another. Which one should we believe?

A definition of science reads – ‘the systematic study of the structure and behaviour of the physical and natural world through observation and experiment’, in other words, an iterative and empirical process within which findings are modified and refined according to the data. Science then can review its position as evidence changes. Scientific knowledge is taken as fact until it is superceded by better knowledge.

Application is a key factor, whether scientific findings based on evidence apply in all circumstances. Does what happens in the laboratory, hold true in the real world? After all, science is supposed to tell us about the physical and natural world.

Are we right to have unquestioning faith in the veracity of science presented as fact? Well, it appears that on occasion the comparative statistics related to our covid situation have been missing some figures. Not comparing like with like, under-reporting, exclusions, missing data due to human or computer software limitations, are all known issues. In this current global example of attempts to ‘follow the science’, there are many potential caveats to the figures we are presented with as reliable truth.

Another issue is the extent to which observation and experiment is possible in real-world situations. The moral dimension prescribes what is acceptable for experimentation in the empirical domain – e.g. whether we can knowingly withhold treatment that we know to be efficacious, from human subjects, in order to test a hypothesis. Limiting experimentation in this way means we have to rely on conjecture rather than evidence.

The process by which scientific fact becomes established and defended as accepted truth can sometimes be very unscientific. Closed minds can be significant barriers to the advancement of knowledge. Let’s not forget the 1633 charge of heresy against Galileo for proving and declaring that the Earth orbits the sun. How about the anti-vaxxer protests? We choose our science to support the truth we want to believe. All in all, it seems science is problematic.

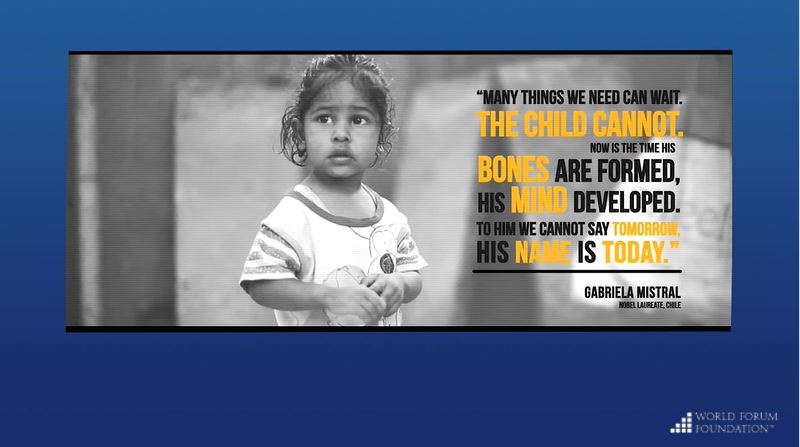

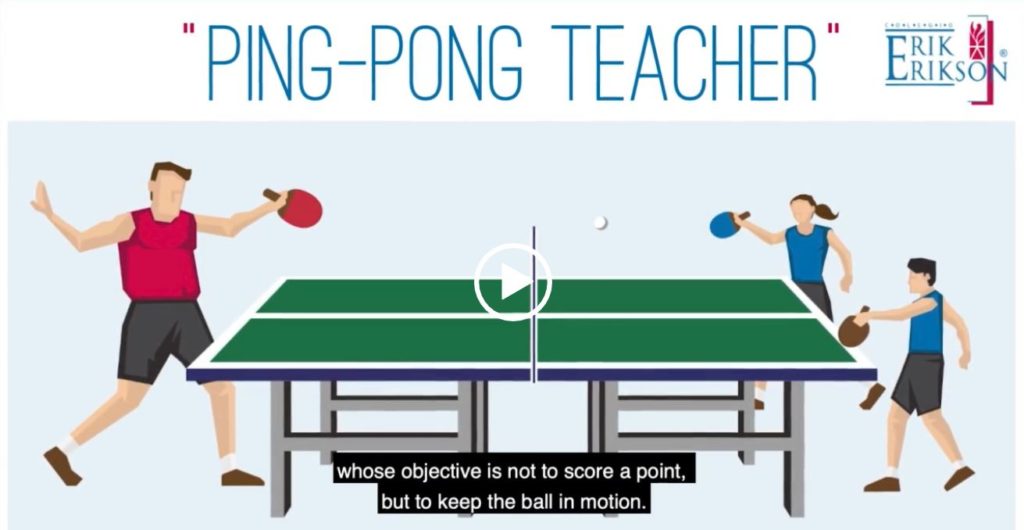

What about education? In recent times, I have observed the promulgation and adoption of cognitive science – the interdisciplinary, scientific study of the mind and its processes, to shape education policy. Typically, cognitive science is used to justify pedagogies and teaching approaches on the basis that it is evidence-based. Once again, there is a need to distinguish the difference between a pure scientific model and applied practice. Context including the role of emotions, personality, environmental factors, motivation and the relationship between the learner and the teacher are all excluded from the theoretical models. We know that the brain is a highly complex organ with many interdependencies affecting its operation and ability to process, retain and to recall knowledge. It is not simply a single dimensional calculator or computer with a dedicated storage device. Emotions matter. How a child feels and in particular, their attitude and ability to engage with the learning process, are key. There are many articles on the subject of the impact of different learning approaches. It is recognised that when an individual feels that they are able to make meaningful choices, they are happier and their learning improves.

Human behaviour is difficult to encapsulate in a set of universally applicable ‘scientific’ algorithms. We are social creatures who interact with and depend on others. We are all unique in the sense that the brain of each one of us has been built and continues to adapt and grow in response to a unique set of stimuli detected, processed and responded to by our ever-changing brain. Nobody else has lived an identical existence with the same combination of genetic make-up, character, knowledge, memory, cognition, brain capacity, emotional and environmental experience. This is why the principles of the Early Years Foundation Stage refer to the Unique Child, Positive Relationships and Enabling Environments. All 3 of these have a bearing on our learning. It is not possible to apply a one size fits all approach based on a narrow interpretation of a cognitive science model to teaching and learning. It’s far more complex than that.

Claims are made that evidence-based practice is the most effective method of teaching. Even where that evidence is ‘robust’ – based on meta-analyses or systematic research reviews, it still begs the question whether the evidence has taken the factors above into account. Does this evidence hold true in all situations for all children? Calm, interested, well-fed, self-regulated children with attentive, supportive and loving parents? Stressed, hungry, dysregulated, abused, neglected, bullied, scared, grieving, sick, discriminated against, otherwise traumatised children? Children in the care system? Children who have broken hearts? Neurodiverse children? Children who cannot tolerate noise; who are unable to sit for long periods; who find it difficult to concentrate? Does the evidence base encompass all of these? Does it include all of us on our good and our bad days? If not, then we can’t use it to apply general rules to anything. We have to apply what we know and have learned about human relationships to the nurture care and development of the unique individual, mindful of their circumstances and experiences.

Maybe we need to be careful in our application of science?

Next slide please!